Critical appraisal skills

Critical appraisal of the existing research evidence is an essential step in the evidence-based practice process.

When health practitioners practice evidence-based practice “the best available evidence, modified by patient circumstances and preferences, is applied to improve the quality of clinical judgements.” (McMaster Clinical Epidemiology Group, 1997)

This is an ongoing process in clinical practice.

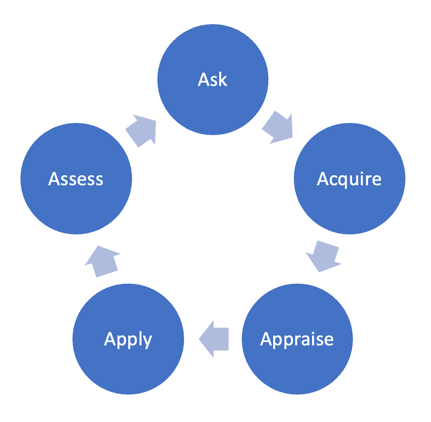

The 5 A’s of the evidence-based practice process

- Ask a specific and well-defined question. For more information on constructing a clinical question, see: Developing researchable questions.

- Acquire the best evidence to answer your question. This will involve searching databases.

- Critically Appraise the evidence you acquire.

- Apply or integrate the appraised evidence with your clinical expertise and your patients’/clients’ unique values and circumstances. This may include implementing a new intervention, creating a new policy, or updating clinical pathways.

- Assess the effectiveness of the intervention or decision.

What is critical appraisal?

Critical appraisal involves examining research evidence to judge its quality based on:

- Trustworthiness: Can we believe the results that are reported?

- Value: How valuable is this research given what is already known about the topic?

- Relevance: How does the evidence relate to the local practice or policy issue identified?

Critical appraisal skills enhance our ability to determine whether research evidence is free of bias and relevant to our patients/clients, and therefore, whether we should use it in our practice. It is important to remember that not all peer-reviewed research will be relevant or have high levels of trustworthiness and value.

Critical appraisal also helps us to identify the gaps or shortfalls in the existing research evidence, which is important when developing a research proposal, protocol, or grant application.

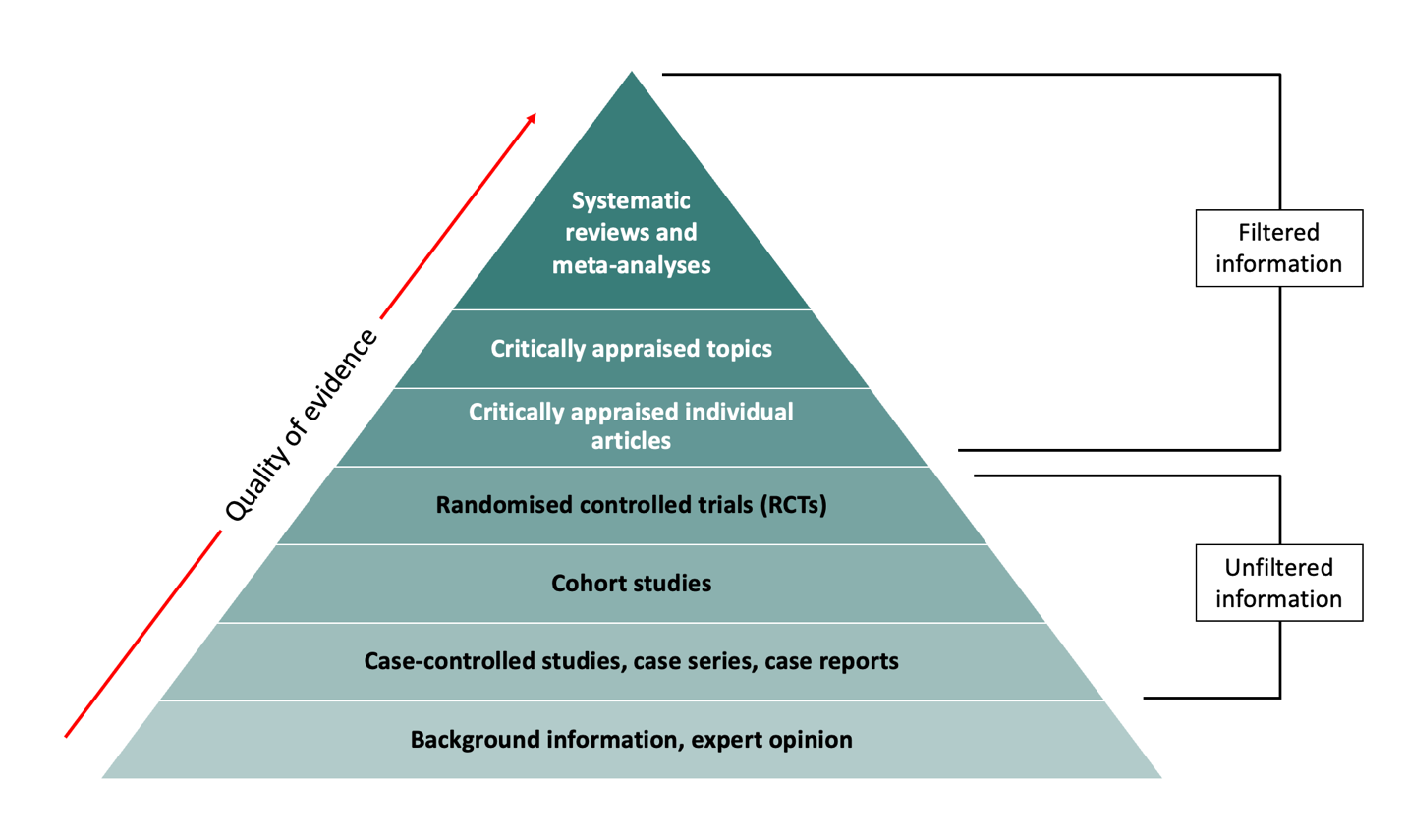

Levels of evidence

The levels of evidence pyramid (or hierarchy of evidence) is one way to understand the relative strength of results obtained from research. As you go up the pyramid, the quality of the evidence increases. You might not always find the highest level of evidence to answer your question. When this happens, work your way down the pyramid.

Filtered Vs Unfiltered Information

Filtered (secondary) resources appraise the quality of multiple studies and synthesise the findings. They often make recommendations for practice which can be used in clinical decision-making. Filtered levels of evidence include:

- Systematic reviews and meta-analyses

- Critically appraised topics

- Critically appraised individual articles

Unfiltered (primary) resources describe original research. They are often published in peer-reviewed journals however have not undergone additional review beyond that of peer-review. In most cases, unfiltered information is difficult to apply to clinical decision-making. Examples of unfiltered levels of evidence include:

- Randomised controlled trials (RCTs)

- Cohort studies

- Case-controlled studies, case series, and case reports

Systematic reviews and meta-analysis (level 1)

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses are considered the highest quality of evidence because their study design reduces bias and produces more reliable findings.

A systematic review synthesises the results from all available studies on a given topic. Systematic reviews follow a rigorous methodology to identify, select, and analyse all potentially relevant studies. While they are considered the strongest and highest quality of evidence, they are also time consuming and may not always be practical. In some cases, a rigorous systematic review might take years to complete in which findings can be superseded by more recent evidence.

Sometimes a systematic review will contain a meta-analysis. A meta-analysis is the use of statistical methods to pool the results of several studies.

More information on the difference between a systematic review and meta-analysis can be found here.

Examples

- Toews I, Lohner S, Küllenberg de Gaudry D, et al. (2019) Association between intake of non-sugar sweeteners and health outcomes: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised and non-randomised controlled trials and observational studies. BMJ 364:k4718. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k4718.

Critically appraised topics (level 2)

Critically Appraised Topics (CATs) provide a short (1-2 pages) summary of the best available evidence on a particular topic. A CAT is essentially a shorter and less rigorous version of a systematic review. Because it is less rigorous than a systematic review, a CAT may be less comprehensive and more prone to bias.

Example

- Cagle JA, Overcash KB, Rowe DP, et al. (2017) Trait anxiety as a risk factor for musculoskeletal injury in athletes: A critically appraised topic. Int J Athl Ther Train 22(3):26-31. doi: 10.1123/ijatt.2016-0065

Critically appraised individual articles (level 3)

Critically appraised individual articles identify, evaluate, and provide a synopsis of a single study. The articles are selected and rated for clinical relevance by clinicians. Critically appraised individual articles are therefore generally considered to be of excellent quality and have potential to influence standard of practice.

Randomised controlled trials (level 4)

A randomised controlled trial (RCT) involves randomly assigning subjects to either an experimental group or a control/comparison group. The two groups are then followed up to see whether there is any difference in the outcome(s) of interest. A RCT is the most reliable study design for demonstrating cause and effect relationships. However, they are often expensive to run and are not appropriate for all research topics.

Examples

- Stathi A, Greaves CJ, Thompson JL, et al. (2022) Effect of a physical activity and behaviour maintenance programme on functional mobility decline in older adults: the REACT (Retirement in Action) randomised controlled trial. Lancet Public Health 7(4):e316-e326. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(22)00004-4

- Jacka, F.N., O’Neil, A., Opie, R. et al.(2017) A randomised controlled trial of dietary improvement for adults with major depression (the ‘SMILES’ trial). BMC Med 15(1), 23. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0791-y

Cohort studies (level 5)

Cohort studies are a type of longitudinal study that follows a group of people who share a common characteristic (e.g., a condition or demographic similarity) over a period of time. Cohort studies are particularly useful for identifying risk factors and causes of disease. Although a step up in reliability and generalisability, they cannot be controlled experimentally are therefore subject to certain biases.

Examples

- Zhang P., Chen PL, Li ZH. et al. (2022) Association of smoking and polygenic risk with the incidence of lung cancer: a prospective cohort study. Br J Cancer 126(11):1637-1646. doi: 10.1038/s41416-022-01736-3

- Jackson CA, Sudlow CLM, Mishra GD. (2018) Education, sex and risk of stroke: a prospective cohort study in New South Wales, Australia. BMJ Open;8:e024070. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024070

Case-controlled studies, Case series, Case reports (level 6)

These study designs are observational and help identify variables that might predict conditions. A case-control study compares people who have a specified condition or outcome (cases) with people who do not have the condition or outcome (controls). A case report is a detailed report of the presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of an individual patient. A case series is a group of case reports involving patients who share similar characteristics. These studies are usually less reliable than RCTs and cohort studies because showing a statistical relationship does not mean that one factor necessarily caused the other.

Examples

- Joy G, Artico J, Kurdi H, et al. (2021) Prospective Case-Control Study of Cardiovascular Abnormalities 6 Months Following Mild COVID-19 in Healthcare Workers. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 14(11):2155-2166. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2021.04.011.

Background information and Expert opinion (level 7)

Background information and expert opinion can often be found in point-of-care resources such as medical textbooks, handbooks, and reference materials. Background information and expert opinion is important to consult when you need general information about a condition, but it is not always backed by research and can be influenced by opinions.

For more information on study design see: Introduction to research design.

Where does qualitative research fit in the levels of evidence?

Qualitative research does not appear on the hierarchy of evidence because the hierarchy tends to reflect clinical epidemiology. However, qualitative research plays an important role in informing clinical practice and policy, by addressing questions that begin with “how”, “why” and in “what way?”.

Bias

When appraising studies that have used a quantitative design, it is important to consider issues related to bias. Bias affects the validity and reliability of research results, which can lead to false conclusions or misinterpretation.

In quantitative studies, there are many sources and forms of bias that can be introduced in the study design and conduct. Some common examples include:

|

|

Attrition refers to participant dropout over time. Attrition bias occurs when there are systematic differences between participants that remain in the study to those that dropout. |

|

|

Confounding is a distortion of the association between an exposure and an outcome because a third variable is independently associated with both. Confounding suggests there is association where there is none or masks a true association. |

|

Detection bias occurs in trials when groups differ in the way study outcomes are measured. For example, this can occur when outcome assessors are aware of the assigned interventions and/or study hypotheses. This knowledge can unconsciously influence the way outcomes are assessed. Blinding (or masking) of outcome assessors can be important particularly for subjective outcomes. Detection bias can result in the overestimation or underestimation of effect sizes. |

|

|

|

Non-response bias occurs when those that are unwilling or unable to participate in a research study differ from those who do participate. Results may therefore misrepresent characteristics of the population. This bias can be of particular concern in survey studies. |

|

|

Performance bias occurs when participants or researchers are aware of intervention allocation and perform differently as a result. This bias may inflate the estimated effect of an intervention and often occurs in trials where it is not possible to blind participants and/or researchers. |

|

|

Publication bias occurs when the outcome of a research study affects the decision to publish. RCTs may be especially affected by this with positive findings more likely to be published than negative or null findings. Publication bias is an important consideration in systematic reviews and other evidence synthesis. |

|

Recall bias occurs when participants do not accurately remember past events or experiences. Recall bias is likely to happen when the event happened a long time ago or when the participant has a poor memory. |

|

|

|

Selection bias occurs when the participants in a study differ systematically from the population of interest. It is usually associated with observational studies where selection of participants is not random. |

In qualitative research, it is more important to consider and appraise concepts such a rigor and trustworthiness rather than bias. This is due to the inherently subjective nature of qualitative data collection and analysis methods.

Finding the evidence (EBM databases)

There are several specialised databases that contain filtered, high-quality research evidence that practitioners can use to support their practice. Some of these include:

- The TRIP Database (Turning Research into Practice) is a freely accessible database designed to allow users to quickly and easily find high-quality research evidence.

- The Cochrane Library is a collection six databases that contain high-quality, independent evidence to inform healthcare decision-making.

- The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) EBP database is an online resource for healthcare professionals to rapidly access up to date high-quality, reliable evidence on a wide range of clinical and policy topics at the point of care, including 4,500+ JBI Evidence Summaries, Recommended Practices and Best Practice Information Sheets.

- The Campbell Collaboration is an international social science research network that produces high quality, open and policy-relevant evidence syntheses, plain language summaries and policy briefs.

Unfiltered information can be found by searching research databases such as:

- CINAHL – nursing and allied health

- Cochrane Library – systematic review and clinical trials

- Embase – Biomedical and pharmacological

- ERIC – education research and information

- Medline – Life sciences and biomedical

- PscyhINFO – Psychological

- PubMed – Biomedical (free to use)

For more information on constructing search strategies see Literature review & literature searching.

Critically appraising the evidence

A structured approach can be useful when learning how to critically appraise papers, and for consistency, such as when critically appraising papers for a systematic review or as part of a journal club. We recommend using a critical appraisal tool.

Critical appraisal tools allow you to assess the quality of a study against a set of criteria. There are various critical appraisal tools available for free, tailored to different study designs. Some popular critical appraisal tools include:

Critical appraisal tools

Use these tools as a guide when critically appraising a research study:

For more information on bias

- The Catalogue of Bias is a digital resource that summarises biases found in research evidence. The catalogue includes definitions, examples, implications and preventive steps for dealing with bias.

- Galdas, P. (2017) Revisiting bias in qualitative research: reflection on its relationship with funding and impact. Int J Qual Methods 16(1). doi: 10.1177/1609406917748992

Interested in learning how to write a Critically Appraised Topic?

- Callander J, Anstey AV, Ingram JR, et al. (2017). How to write a Critically Appraised Topic: evidence to underpin routine clinical practice. Br J Dermatol 177(4):1007-13. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15873

Training

The Critical Appraisal Skills Program offers virtual workshops and training courses designed for all healthcare professionals.

Journal clubs

Journals clubs are a great forum for developing critical appraisal skills. Check to see if one exists within your organisation.

For tips on how to run a journal club and prepare articles:

- Aronson JK. (2017) Journal Clubs: 2. Why and how to run them and how to publish them. BMJ Evid Based Med 22(6):232-234. doi: 1136/ebmed-2017-110861

TREAT journal club format is a free journal club system you can tailor to use within your team. Several resources are available once your journal club is registered. Evaluation of the TREAT journal club format suggests health professionals were significantly more satisfied using the TREAT format compared to standard journal club and increased interaction and skill development.