Implementation Science

This resource was developed by Dr Anna Chapman, Senior Research Fellow at Deakin University.

The chaotic and complex nature of the health service environment means the implementation and sustainment of new evidence and healthcare interventions can be challenging.

Research suggests that approximately 60% of all healthcare practice and delivery is in line with evidence-based best practice guidelines (Braithwaite et al., 2020). This is concerning, especially in rural and regional health settings, where challenges to implementing and sustaining new evidence and healthcare interventions can be more pronounced.

Implementation science is the scientific study of strategies to adopt and integrate evidence-based health interventions into clinical and community settings to improve individual and population health outcomes. Implementation science helps researchers and healthcare services to reduce the gap between the research evidence and routine practice.

This resource outlines some of the key concepts and practices related to implementation science, that can help emerging researchers to generate and translate evidence in their practice settings, and to improve practice, policy, and ultimately, consumer and community outcomes.

Implementation Science- key concepts

- The intervention/practice/program is THE THING

- Effectiveness research looks at whether THE THING works

- Implementation research looks at how best to help people/places DO THE THING

- Implementation strategies are the stuff we do to try to help people/places DO THE THING

- Implementation outcomes are HOW MUCH and HOW WELL they DO THE THING

Adapted from: Curran, G.M. (2020). Implementation science made too simple: a teaching tool. Implementation Science Communications 1.1: 1-3.

Visual depiction of key implementation science concepts

Theories, models, and frameworks

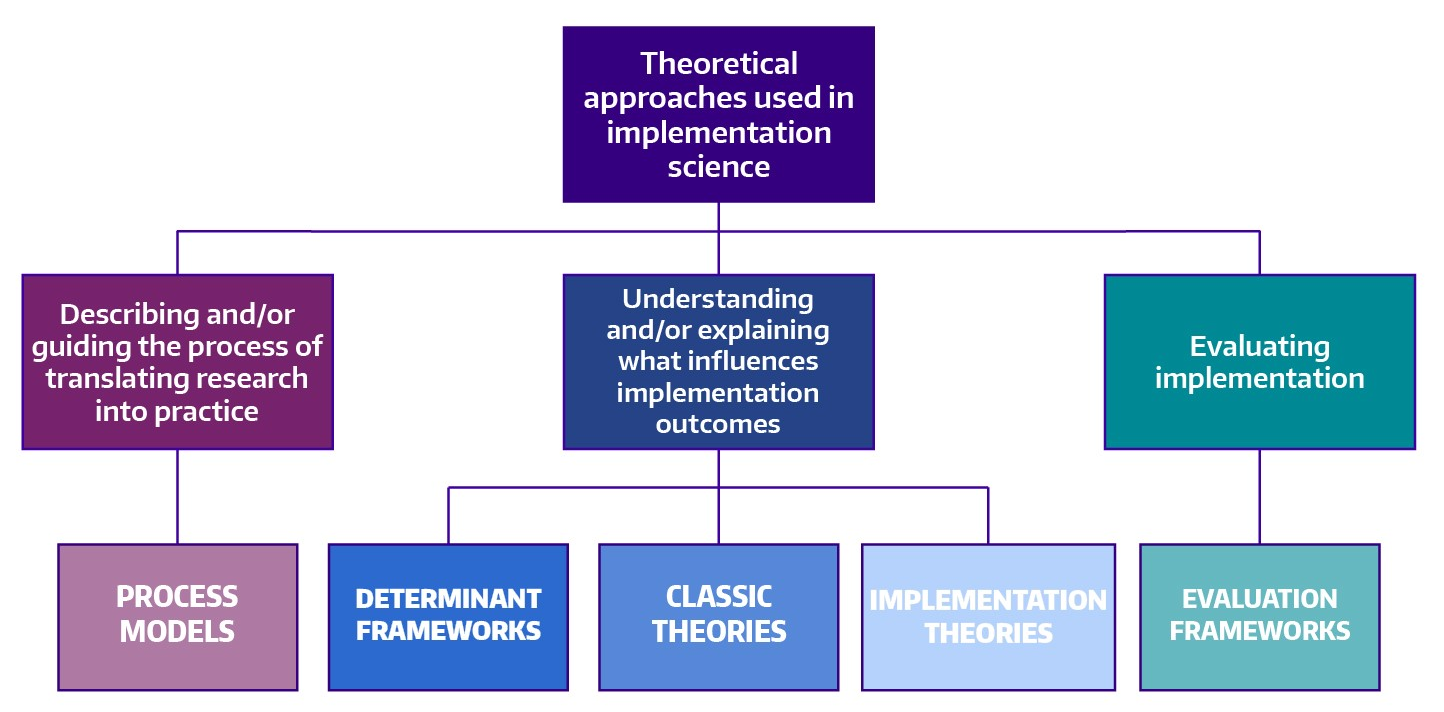

Theories, models, and frameworks each play an important role in informing and guiding implementation activities. However, with more than 100 implementation theories, models, and frameworks, it can be very overwhelming trying to work out where to begin.

Theories, models, and frameworks each serve a different purpose in implementation. You don’t need to use all types of theories, models and frameworks – it is important that you select one that is fit for purpose. There are different theories, models and frameworks for different purposes:

Image Source: https://impsciuw.org/implementation-science/research/frameworks/

Examples of Theories, Models and Frameworks

|

Category |

Examples |

|

Process models |

Knowledge-to-Action (KTA/K2A) Framework EPIS (Exploration, Adoption/Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment) Framework |

|

Determinant frameworks |

Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) |

|

Classic theories |

Diffusion of Innovations Theory Various social cognitive theories; organisational theories; psychological theories etc. |

|

Implementation theories |

Behaviour Change Wheel, including COM-B (Capability, Opportunity, Motivation – Behaviour) Normalization Process Theory (NPT) Organisational Readiness for Change |

|

Evaluation frameworks |

Proctors Implementation Outcomes Framework RE-AIM Framework (Reach, Efficacy, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance) |

Five practical steps to address an implementation research problem

There are five practical steps to address an implementation problem in your health service; these steps span from pre-implementation through to the post-implementation phases. Researchers do not need to address all of these steps in a single project. In some cases, each of these steps can be a discrete research project. The implementation steps are summarised under the five subheadings below.

The first step involves clearly identifying and defining the implementation problem, by investigating:

- What evidence-based best practice is relevant to the clinical or service delivery area; that is, what the guideline or strong and compelling evidence suggests. Hint: check out STaRR Critical appraisal skills for more on evaluating the evidence)

- What is currently happening in practice

It is important to consider micro level (point of care), meso level (organisation), and macro level (health system) factors influencing the current practice/s.

During this step, it is important to access and utilise local data as evidence of the current practice and the implications (e.g., wait list data, frequency of adverse events, unexpected staff leave, failure to attend rates, etc.) of continuing current/non-evidence-based practice.

Leading on from this, researchers/implementors must identify what needs to be done differently in order to align with evidence-based best practice. This will help to determine the “intervention” or the “thing” that represents the change from current to evidence-based best practice. For example, this might be a new model of care, adherence to clinical practice guidelines, etc.

Once the intervention is identified, it is important to consider if the intervention needs to be adapted to the local setting. This can be determined by examining:

- The resources available (staffing, physical infrastructure, costs, time)

- Current workflows and processes

- The complexity of intervention (all the moving parts and people/roles/teams implicated in the current and evidence-based best practice model)

- The ‘core’ and ‘adaptable’ components of the intervention

- The relevant stakeholders and ensuring appropriate consultations are undertaken to adapt the intervention

- The most appropriate and feasible format for consultation within the health service setting

It is important to identify the various factors, including enablers and barriers, that influence implementation of the intervention by using one or more of the following processes or resources:

- Qualitative methods to gather data (interviews, focus groups, etc.)

- Quantitative methods to gather data (surveys, observation, etc.)

- Hint – check out STaRR Research design for some more on research design and methods

- Determinant frameworks can help guide this step (e.g., Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research, Theoretical Domains Framework) by providing a structure for the approach to gathering and analysing data (guiding the development of surveys and interview/focus group guides, and the data coding/categorisation process – hint check out STaRR Qualitative data analysis for more information)

It is important to note, researchers/implementers may identify many barriers and facilitators to implementation. To avoid getting bogged down, it is important to prioritise the most impactful of these and plan accordingly.

Some examples of facilitators of implementation in rural and regional settings include:

|

Facilitator |

Description |

|

Leadership |

Leadership engagement, buy-in, and support; facilitated adequate resourcing, clear communication, and encouraged staff buy-in |

|

Education |

Regular training and orientation of new staff facilitates implementation → reinforces new processes, awareness of intervention, and assists sustainability |

|

Academic affiliations |

Enhances ability to access new knowledge, resources, and attract staff |

|

Champions |

Strong clinical champions → increased support and motivation, and staff buy-in |

|

Sense of Community |

Staff are personally invested, have pre-existing relationships with community/patients → greater commitment and desire to collaborate when resources are limited |

|

Adaptability and creativity |

Ability to adapt intervention to context enhanced implementation Rural settings perceived to have flexibility to adopt new interventions/be creative |

|

Reflecting and evaluating |

Collecting and reflecting upon data to determine success of implementation e.g., audit data Sharing of data across departments/networks can enhance motivation e.g., benchmarking |

|

Networks |

Internal and external networks → access to information/resources/support Informal networks, facilitated by existing relationships and co-location of services |

Some examples of implementation barriers to implementation in rural and regional settings include:

|

Barrier |

Description |

|

Resources |

Staff workload, time constraints, staff shortages and turnover Lack of funding, locally relevant resources, infrastructure (physical, IT) |

|

Access to appropriate specialists/services |

Limited access to local specialists and services → impacting screening/assessment practices, and implementation of care pathways and guidelines Some services are available, but many are at capacity Lack of culturally appropriate services (e.g., for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities) |

|

Intervention integration and complexity |

Interventions that don’t fit into existing workflows, processes Intervention complexity made integration challenging |

|

Staff commitment and attitude |

Interventions perceived as not being relevant to rural context, needed, better, or important to staff → decreased staff buy-in and motivation, and ultimately engagement Not engaging staff early, or communicating ‘need’ → staff feeling undermined, unskilled |

|

Knowledge and Information |

Lack of training and awareness of intervention processes, particularly where staff turnover and workload is high → impacting staff skills, ability and confidence |

This step involves reflecting on the enablers and barriers identified in the previous step, then designing and using strategies that will support implementation of the intervention, accordingly.

There are tools that help to match enablers and barriers to implementation strategies, for example:

- If the Theoretical Domains Framework is used – the theory and techniques tool

- If the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research is used – the CFIR-ERIC matching tool

Ideally, implementors will work with stakeholders to tailor the implementation strategies to the target audience. For example, if education or training is identified as the strategy to address an identified knowledge barrier, stakeholders can be consulted to design the format, content, frequency of training.

Once the implementation strategies are designed and ready to go, it is time to implement the strategies and the intervention.

This step involves evaluating the implementation efforts. Researchers/implementers can use qualitative and/or quantitative methods to evaluate implementation outcomes. Implementation outcomes are distinct from clinical/health outcomes or service outcomes.

Evaluating the implementation outcomes helps researchers/implementors to distinguish between ‘intervention failure’ (i.e., the intervention is ineffective in the setting) and ‘implementation failure’ (i.e., intervention is effective, but not implemented well).

An evaluation framework can be helpful at this stage (e.g., Implementation Outcomes Framework, or the RE-AIM framework)

Researchers/implementors can measure many different implementation outcomes, however it is not necessary to measure all of them. Evaluating implementation outcomes takes time and requires resources, so researchers/implementors must be strategic about how they approach evaluation. It is recommended that researchers select and measure implementation outcomes that are aligned to their specific question.

Resources, papers and references

Resources

- Dissemination & Implementation Models in Health Research & Practice: An interactive, online webtool designed to help researchers and practitioners navigate D&I Models through planning, selecting, combining, adapting, using, and linking to measures. https://dissemination-implementation.org/

- Implementation Outcome Repository: A free, online resource for implementation stakeholders, including researchers and healthcare professionals, wishing to quantitatively measure implementation outcomes. https://implementationoutcomerepository.org/

- UW Implementation Science Resource Hub: An online platform that includes information and resources on core elements of implementation science. https://impsciuw.org/

- Theory & Techniques Tool: An interactive heat map that provides information about links between behaviour change techniques (BCTs) and their mechanisms of action (MoAs). Can be used to guide researchers and practitioners in the selection of BCTs for their relevant barriers/facilitators. https://theoryandtechniquetool.humanbehaviourchange.org/

Papers

Introductory Papers

- Bauer, M. S., Damschroder, L., Hagedorn, H., Smith, J., & Kilbourne, A. M. (2015). An introduction to implementation science for the non-specialist. BMC Psychology, 3(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-015-0089-9

- Shelton, R. C., Lee, M., Brotzman, L. E., Wolfenden, L., Nathan, N., & Wainberg, M. L. (2020). What Is Dissemination and Implementation Science?: An Introduction and Opportunities to Advance Behavioral Medicine and Public Health Globally. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 27(1), 3-20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-020-09848-x

- Rapport, F., Clay-Williams, R., Churruca, K., Shih, P., Hogden, A., & Braithwaite, J. (2018). The struggle of translating science into action: Foundational concepts of implementation science. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 24(1), 117-126. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.12741

Theories, Models and Frameworks

- Nilsen, P. (2015). Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implementation Science, 10(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0

- Tabak, R. G., Khoong, E. C., Chambers, D., & Brownson, R. C. (2013). Models in dissemination and implementation research: useful tools in public health services and systems research. Frontiers in Public Health Services and Systems Research, 2(1), 8. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/frontiersinphssr/vol2/iss1/8/

- Lynch, E. A., Mudge, A., Knowles, S., Kitson, A. L., Hunter, S. C., & Harvey, G. (2018). “There is nothing so practical as a good theory”: a pragmatic guide for selecting theoretical approaches for implementation projects. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 857. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3671-z

Implementation Strategies

- Leeman, J., Birken, S. A., Powell, B. J., Rohweder, C., & Shea, C. M. (2017). Beyond “implementation strategies”: classifying the full range of strategies used in implementation science and practice. Implementation Science, 12(1), 125. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0657-x

- Powell, B. J., Waltz, T. J., Chinman, M. J., Damschroder, L. J., Smith, J. L., Matthieu, M. M., Proctor, E. K., & Kirchner, J. E. (2015). A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implementation Science, 10(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1

- Waltz, T. J., Powell, B. J., Matthieu, M. M., Damschroder, L. J., Chinman, M. J., Smith, J. L., Proctor, E. K., & Kirchner, J. E. (2015). Use of concept mapping to characterize relationships among implementation strategies and assess their feasibility and importance: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) study. Implementation Science, 10(1), 109. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0295-0

- Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). EPOC Taxonomy; 2015. https://epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-taxonomy

Implementation Outcomes & Study Designs

- Proctor, E., Silmere, H., Raghavan, R., Hovmand, P., Aarons, G., Bunger, A., Griffey, R., & Hensley, M. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 38(2), 65-76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7

- Brown, C. H., Curran, G., Palinkas, L. A., Aarons, G. A., Wells, K. B., Jones, L., Collins, L. M., Duan, N., Mittman, B. S., Wallace, A., Tabak, R. G., Ducharme, L., Chambers, D. A., Neta, G., Wiley, T., Landsverk, J., Cheung, K., & Cruden, G. (2017). An Overview of Research and Evaluation Designs for Dissemination and Implementation. Annual Review of Public Health, 38(1), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurevpublhealth-031816-044215

- Wolfenden, L., Foy, R., Presseau, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Ivers, N. M., Powell, B. J., Taljaard, M., Wiggers, J., Sutherland, R., Nathan, N., Williams, C. M., Kingsland, M., Milat, A., Hodder, R. K., & Yoong, S. L. (2021). Designing and undertaking randomised implementation trials: guide for researchers. BMJ, 372, m3721. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m3721

Grant writing

- Proctor, E. K., Powell, B. J., Baumann, A. A., Hamilton, A. M., & Santens, R. L. (2012). Writing implementation research grant proposals: ten key ingredients. Implementation Science, 7(1), 96. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-96

Reporting guidelines

- Pinnock, H., Barwick, M., Carpenter, C. R., Eldridge, S., Grandes, G., Griffiths, C. J., Rycroft-Malone, J., Meissner, P., Murray, E., Patel, A., Sheikh, A., & Taylor, S. J. C. (2017). Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI) Statement. BMJ, 356, i6795. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i6795

- Proctor, E. K., Powell, B. J., & McMillen, J. C. (2013). Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implementation Science, 8(1), 139. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-139

Online Training

- Training Institute for Dissemination and Implementation Research in Cancer (TIDIRC) OpenAccess: The eight modules below make up the TIDIRC OpenAccess course. Relevant beyond those involved in cancer research. The modules can be viewed together as a whole or individually by section. https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/is/training-education/training-in-cancer/TIDIRC-open-access

- Center for Implementation – Inspiring Change 2.0: A free, self-directed mini-course that shows people how implementation science can enhance how they inspire and support change. https://thecenterforimplementation.teachable.com/p/inspiring-change

References cited in the resource

Braithwaite, J., Ludlow, K., Testa, L., Herkes, J., Augustsson, H., Lamprell, G., … & Zurynski, Y. (2020). Built to last? The sustainability of healthcare system improvements, programmes and interventions: a systematic integrative review. BMJ Open, 10(6), https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/10/6/e036453

Curran, G. M. (2020). Implementation science made too simple: a teaching tool. Implementation Science Communications, 1, 1-3. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s43058-020-00001-z

Nilsen, P. (2015). Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implementation Science, 10(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0